Joan Semmel on Lisa Yuskavage

As an artist I have never wanted to write about art, my own or anyone else’s. I’ve always felt that the art must speak for itself without the embellishment of words. In the hyper art environment and constant propaganda in which we are all now working, the noise surrounding every event makes it almost impossible to really see any art without being influenced by its promotional baggage. How can we utilize the past history of art and the present deluge of images that floods our environment, to create an art that is both meaningful and accessible? Can paint on canvas, and object oriented, essentially contemplative art, have a place in a society of sound bites and multi-tasking? Both painting and figuration have received short shrift in the critical press in the last 20 years, as Performance Art and technology picked up from Conceptualism and Abstraction as the new darlings, seducing the hordes of students entering art schools because they loved to draw and paint. How does art move beyond style and contemporaneity to penetrate the surface of things?

I would like to speculate about some of the issues that I feel have not really been aired much regarding an artist whose work in some ways coincides with my own, although not very comfortably. I was thrilled when Lisa Yuskavage first entered the discourse, as one who survived art school seductions at last. But the price of survival was the use of shock, coated in irony. Irony is a double-edged sword. It engages those who hate and those who love, both at the same time, and all can live together in the same bed. The result then is neutrality, or status-quo.

Yuskavage’s work employs all of the traditional tools of the painter’s art with confidence and élan. Her work will stand up to the scrutiny of the most discerning amongst us. What then is there left to say, except to heap praise upon praise? For many years when writing about any art, critics would concentrate on descriptions-- of the color, the line, above all the style of the work-- and then came the shift of emphasis to the meaning of the work. In later years context was the important measure. So I would like to begin with context.

The English artist Jenny Saville, who uses paint as gesture and surface as well as volume, seems more connected to other English figurative artists such as Lucian Freud; and both of their approaches to painting register as an outgrowth of the distortions of a De Kooning woman and a return to the power of volume within the tradition of contemporary painting. In conceptual and generational terms they predated Yuskavage in expressing a highly personal way of treating representations of the human form without depending on stylistic novelty for impact.

Yuskavage, on the other hand, appeared and was educated at Yale School of Art at the same time as John Currin, and their works were often linked because of the almost cartoonish nature of the way they depicted the figure and their relationship to the appropriation of art history, advertising and pornography. Both adopted approaches that were rooted in the ideas of Warhol and Jeff Koons and featured slick surfaces and super cool emotional resonance. I have to admit that I could never get past what I considered mockery in the works of both--not mockery of their sources, but of their subjects and audience. What then is the difference between irony and mockery? I would posit that Irony has a different bite. It returns us to the source issue that is being criticized. Mockery leaves us with a sneer.

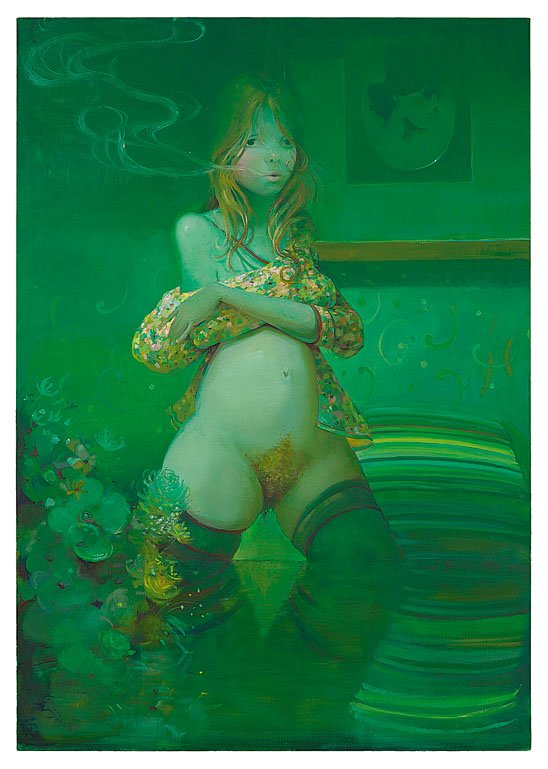

I went to see Yuskavage’s last show at Zwirner Gallery hoping to find a maturation of theme to measure up to her sumptuous color and fluid paint quality. The works on paper, I found, experimented with using descriptive form in a looser way, flooding the whole page with one ground color and then working linear elements into that ground, finding and losing edges. Some of those methods were extended into the paintings, where a monochromatic ground color held all the elements in play. The use of deep space gave a somewhat otherworldly quality to scenic settings in which the narratives were placed, although in some pieces the figures were up tight against the picture plane and seemed to be onlookers to the background activities.

Yuskavage’s preoccupation with doll-like creatures with upturned noses, distended stomachs, nipples pointing in separate directions at the sky, and engaged in Game of Thrones-like narratives is present in most of the paintings. The rounded buttocks, paste-on breasts and occasional bust in the viewer’s eye sometimes make the paintings feel like illustrations for a fantasy publication. The abject child woman, projected in much fashion photography, is exaggerated here to even more extreme ends. The color becomes an environmental envelope, sometimes grisaille, punctuated by several luminous, contrasting elements. The soft focus of disappearing outlines refers to photographic and film sources. The accompanying literature for the show carefully cites Renaissance references and folkloric narratives as sources for some of the material.

What then are we supposed to make of all this? Are these paintings an attempt to make the viewer uncomfortable or an attempt to seduce us into vicarious pleasure? Are they a way of thumbing one’s nose at all possible pieties? Although the aging male figure in ”Dude of Sorrows” sports a black eye and a collapsed penis, the cute female figures, with their preadolescent bodies engaged in adult sexual provocations seem more seriously damaged psychically. Is her work a form of self-hatred finding voice? Do young women identify with these creatures, or is her work a form of critique that I am missing? Is Yuskavage simply pandering to the usual art world-savvy audiences?

I think that perhaps there is some of each of these elements involved. I would not presume to speculate on the psychological underpinnings of the artist’s intentions, but I think that self-hatred misses the mark. The artist was groomed in the Yale School of Art MFA Program, a very savvy art school. Her work originally surfaced when Feminism was in a backlash phase. In a culture where women have been infantilized and made to be dependent for so long, the necessity for women to suddenly become independent and responsible can be daunting. Young women’s yearning to regain their lost childhood without losing the sexual freedoms gained in the new independence is perfectly symbolized in Yuskavage’s images. Men have usually found vulnerability and childish innocence enormously appealing sexual attributes; thus these images work their seductive magic on all sexes. She has used perfect timing and strategy to appeal to a wide audience of both the super cool and the somewhat regressive. Now that the culture seems to be entering a new Feminist phase perhaps we can question some of these attitudes and their crippling effects. We need a new Zeitgeist.

Yuskavage’s paintings are aesthetically and technically accomplished but, to me, profoundly disturbing. Perhaps that, in the end, is their strength.